MAPUCHE

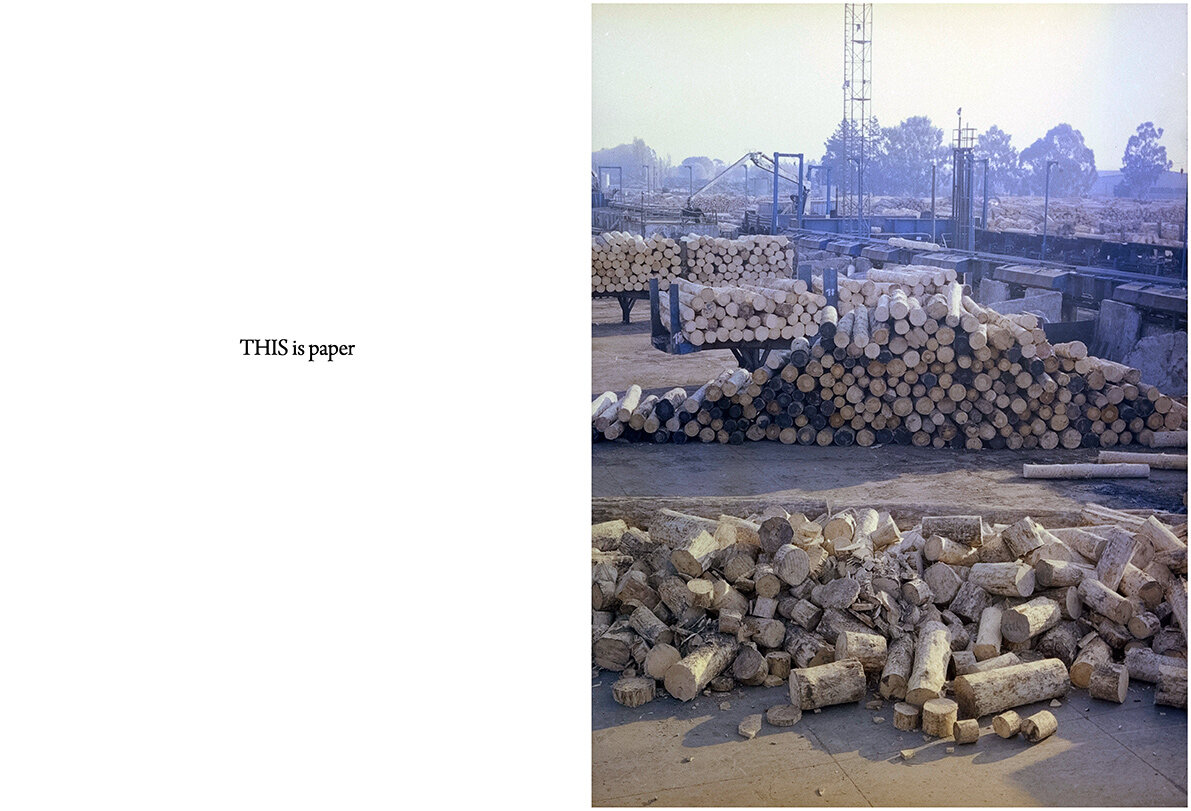

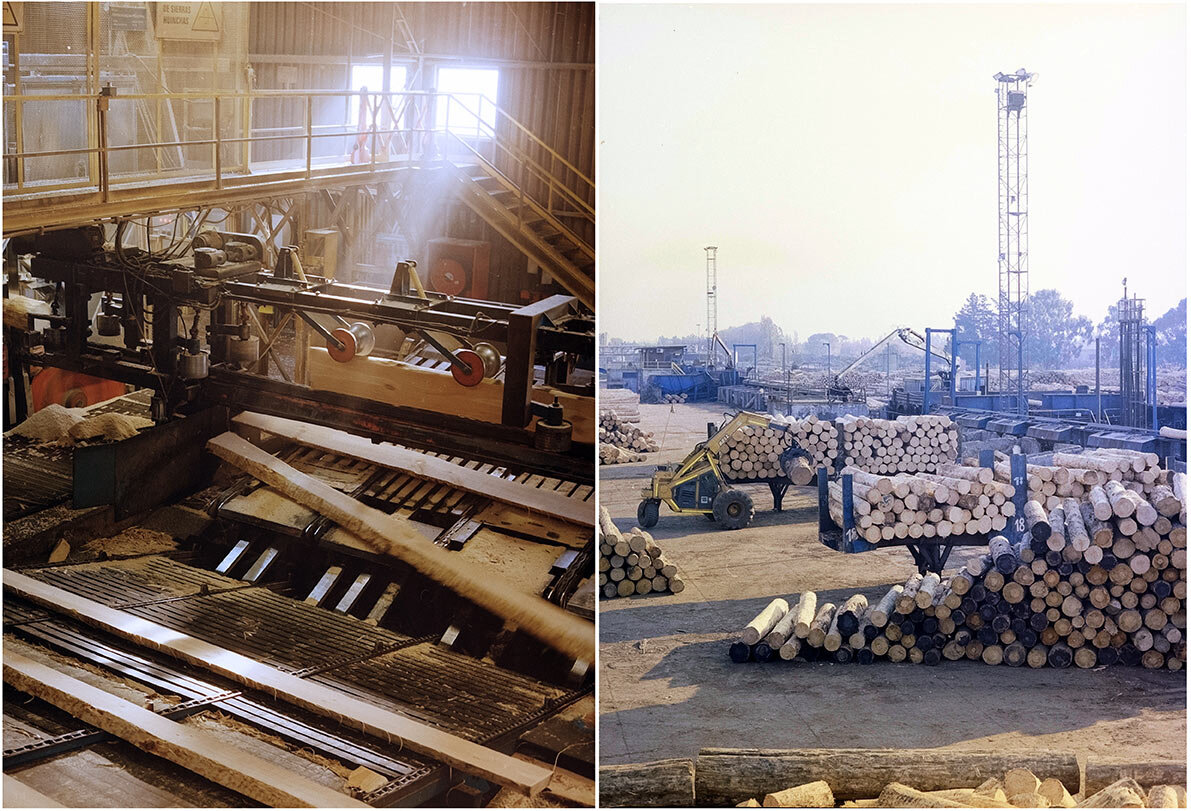

Chile is the world's fourth largest producer of paper pulp with 8% of world production spread over 2.87 million hectares of forest plantations. On these lands that have always been inhabited by the Mapuche people from the south of present-day Chile and Argentina, there are two world views in tense coexistence: one based on the global market economy and the exploitation of natural resources, and the other in which the relationship with the environment is a spiritual issue. In the midst of these two worlds, medicinal plants that have survived for centuries have become faithful witnesses to an endless cycle of construction and destruction. They suffer the consequences of the upheavals in the ecosystems. To listen to them is to understand the notion of territory by going to the epicentre of the political and ecological conflict that the Mapuche and Chileans are experiencing today.

Ritual Inhabitual carried out a 5-year project, both ethnobotanical and artistic, photographing on Wet Collodion plates (a 19th century photographic process) and on large and medium format colour negatives, members of the Mapuche community, plants, trees and cloning laboratories of a forestry company. They question ethnographic and scientific methods while affirming the documentary gesture of photography. In this way they bring to light the relationship that the Mapuche people have with plants and the relationship between forestry companies with the environment despite the fact that native communities are endangered by monoculture systems and by the territorial policies of states

SERIES

Ritual Inhabitual's collective and collaborative work has brought people from different sectors into the research process: a curator, two ethnobotanists, an ethnomusicologist, a writer, an ecologist, a graphic designer. The works resulting from this work are made up of 3 series in 3 formats: Large and Medium Format on colour negative, Wet Collodion on glass plate and High Definition Scans.

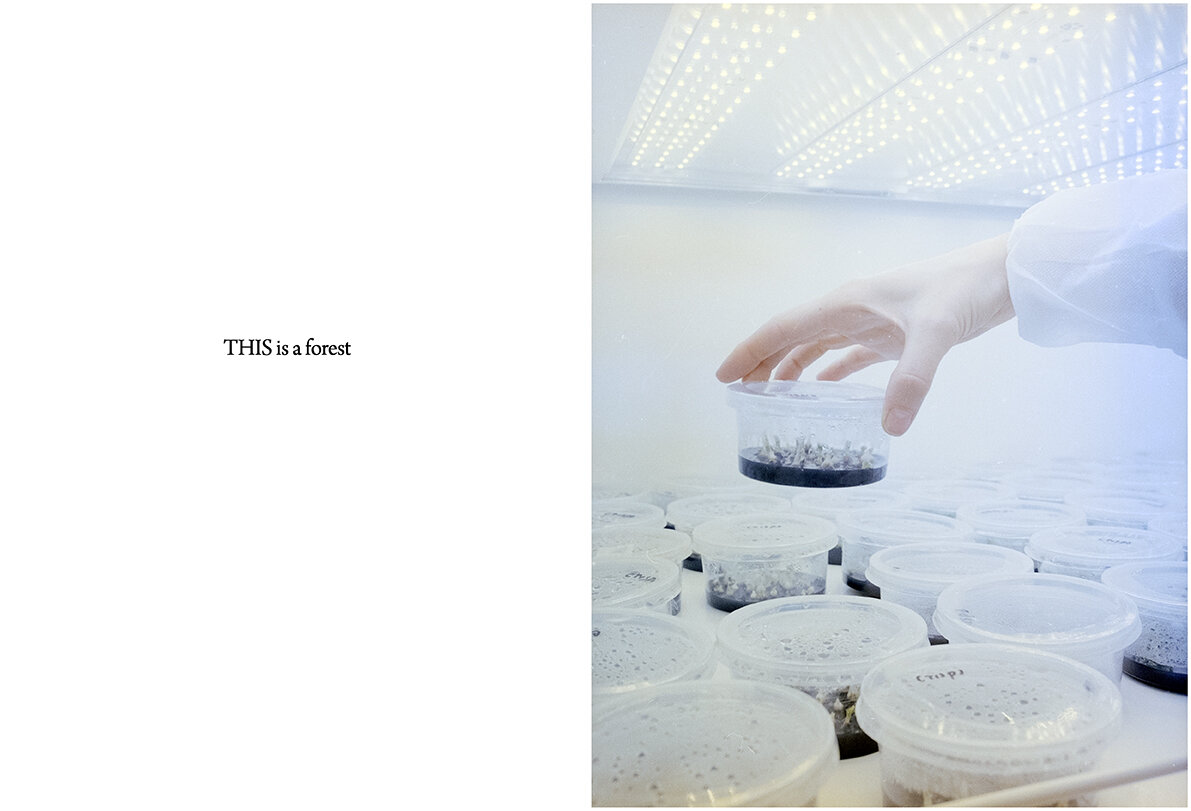

Large and Medium Format on Colour Negative

We followed the cloning, planting and extraction of trees at a high-tech cellular copying laboratory. Clones are developed for the yearly planting of seedlings on plantations, through cell multiplication. This is done by a specific monitoring of each seed and the subsequent extraction of the cell copies that are sent to the field. After five years, the performances are analyzed, and then the best individuals are selected to be multiplied, increasing the productivity of the plantations by 40%.

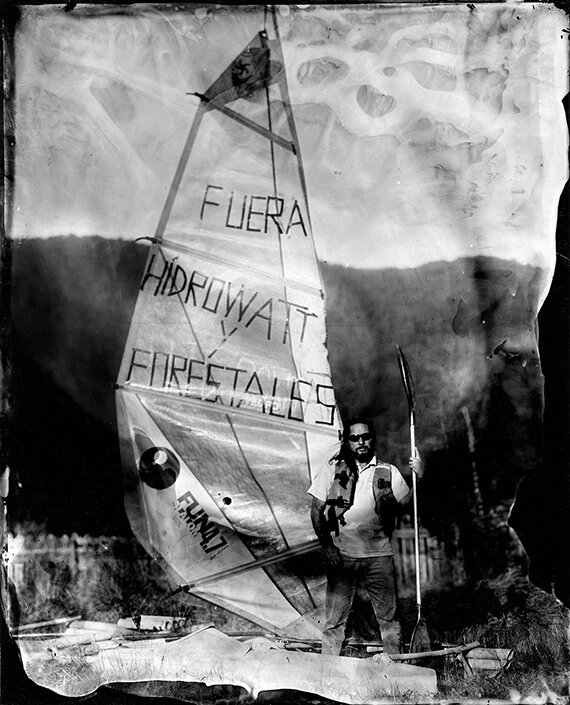

Wet Collodion on Glass Plate

For 4 years we spent periods immersed in the Lafkenche communities of Lake Budi, Lake Lanalhue in the Araucania and Bio-Bio regions, creating portraits of spiritual and social figures. During this time, we also photographed the musical and political movement of Rap Mapuche in the suburbs of Santiago and south of Temuco. Finally, we made a herbarium of medicinal plants on glass plate.

High Definition Scans

Researcher Flora Pennec created a herbarium of Mapuche medicinal plants during a trip in 2016 with Ritual Inhabitual and in collaboration with the MNHN (The National Museum of Natural History) in Paris and the Eco-Antroplogy Laboratory of the Musée de l'Homme. The plates of the collected herbarium (a version was deposited at the MNHN in Santiago de Chile in 2016) were scanned on an HERB-SCAN, then integrated into the collection of the Herbier Nationale de France in 2017.

Wet plate processed photographs (Collodion)

Click on the image to see it in detail.

This is a photographic study of the participants in the main rituals of the Mapuche people. It started in January and February 2015, following a trip to the south of Chile, to the Amerindian communities of Lake Budi in the Araucanía region. Now, in 2016 the project has grown to include Catholic and Evangelical communities and young rappers from the suburbs of Santiago. After two long years we finally realized that all their bonds are woven into their relationship with nature, and thus, in their use of plants. Mapuche, indeed, means Man (Che) of the Earth (Mapu).

Between 1881 and 1883, Chile carried out a campaign of "pacification". This was nothing short of a militarized invasion of Indian territory that had previously enjoyed autonomy established in an agreement with the Spanish crown. These dates mark the beginning of the bloody conflict between the state of Chile and the Mapuche people, which is ongoing today.

We decided to work on the collodion wet plate process, a technique dating from 1851. Because during the time that Mapuche populations were being decimated in Chile and Argentina, in the USA (from 1880-1890) photographers would cross the plains photographing Indian Chiefs using this same technique, most likely because they felt that the building of the nation would be based on the annihilation of local people. For this reason these photographs would be associated with ethnographic works of the late 19th century. Although today we know that some of these photographers often staged their subjects without respecting the cultural, or social codes of the tribes, wet collodion keeps its purely documentary nature.

Our interest today is that the collodion process questions how ethnographic methods contributed to the representation (true or false) of the people and places that anthropology was trying to describe.

Photography using the collodion process is achieved by long exposures during shooting, but the real constraint is that the preparation and development of the glass plate must be done at the same time and at the same place. This time creates a special relationship between the person photographed and the objective of the photographic camera. Additionally, for spiritual reasons firstly and secondly historical, the Mapuche don’t easily allow themselves to be photographed. For shamen it can cause illness and may also, in the worst cases, cause sudden death, often through accident. This technique is doubly complex because in fact, the subject and camera are alone face to face during the time of the chemical preparation and development, pushing the person to go into a trance in which she may lose control her own image. The result is not the condensation of a gesture, but rather a state of mind that is born in this photographic time and that seems completely outside of time.

It often took days or even weeks of discussions and relationship management to convince the Mapuche to be photographed. That time when they were alone with the camera was always a critical one: either the subject understood that he had made a mistake, or he opened the door of his confidence and in this way gave us his experience, knowledge or feelings. All we have learned from an ethnographic point of view, was then concocted in this fragile moment of waiting during the making of a portrait.

More than trying to represent the Mapuche people, we used photography to describe a joint work between subject and photographer. It is interesting to observe how the ethnographic photography, lacking in scientific method, can be a protest in the face of the construction of the collective imagination. But in this project; the collective imagination is given freely by the subject. During our work some people agreed to be photographed only if they were able to decide how they would be represented. The climax of this situation was in Santiago when a young rapper brought us a 1908 photograph, telling us she wanted to appear exactly as the Native American in the photo (a woman breastfeeding her child). Our own fears and our aim to be objective were then overtaken by what could be called the "representation of representation," and it came from the subject not the photographer.

The purpose of this work is for these images to become social objects that describe a particular time and space. In Chile, some people are interested in the dynamism of the Mapuche culture that has been able to adapt to all kinds of geopolitical change. This is why each of our meetings with the representatives of the Mapuche people were a link allowing us to meet new people that helped us build a genealogy, and although this is not sufficient to be regarded as a representation, it is nevertheless an impression left by the reality of a journey, an immersion into complex entities.

We hope to contribute to the discussion on how Chilean society could change its approach to the Mapuche people, taking into account global change and geopolitical issues that tend toward the protection of the environment.